Two California researchers aim to gain a real-time understanding of homelessness using a perhaps unexpected resource found among the homeless: smartphones.

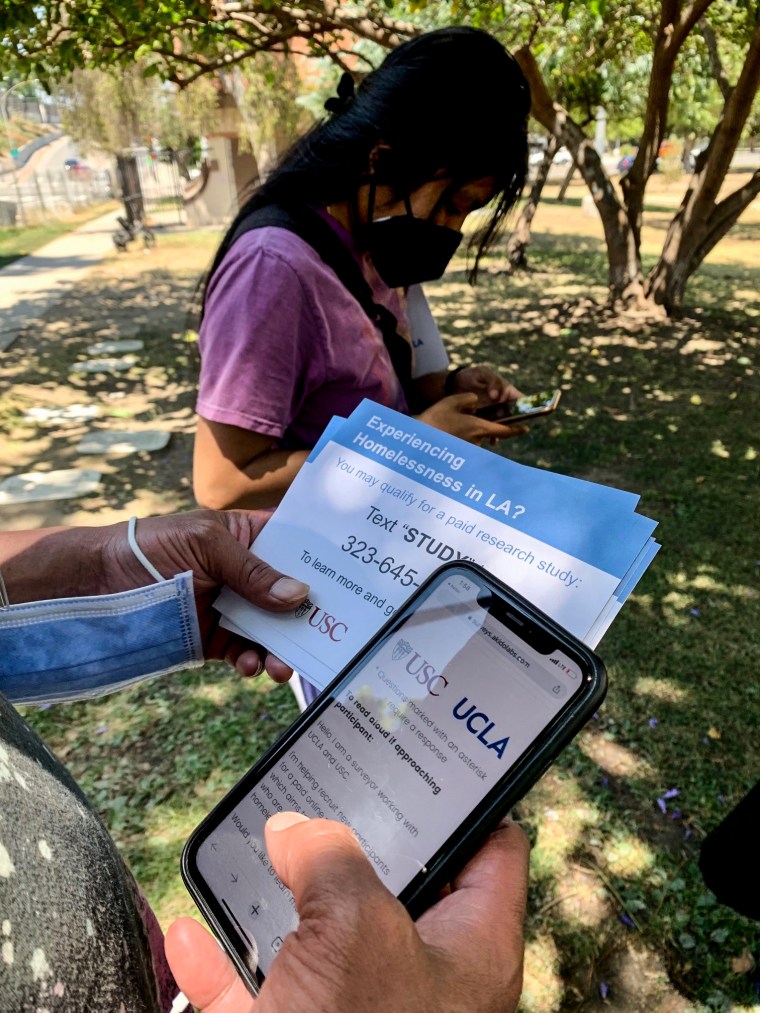

Benjamin Henwood, an associate professor of social work at the University of Southern California, and Randall Kuhn, a professor in the department of community health sciences at UCLA, began a research program that surveys a sample of homeless people in the county. Los Angeles on a monthly basis through their phones.

Seeking to go deeper than previous general studies, the survey contains questions focused on individual preferences related to permanent housing, community shelters, and exposure to law enforcement.

«Asking what people are looking for in their preferences is useful because there’s no hard data on it, and it disproves a lot of myths about people,» Henwood said.

Efforts come as homeless. still a major problem in many parts of the US, especially on the West Coast. Almost 30% of homeless are in California, according to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, with many who live in Los Angeles County.

And while billions of dollars are spent each year on homeless-related programs, there can be a lack of accurate, up-to-date data on what homeless people are experiencing and what their priorities are.

“What are the specific burdens and what can we alleviate?” Kuhn said. «We have no idea how to approach that.»

So Henwood and Kuhn developed PATHS, short for Periodic Assessment of Pathways of Study in Housing, Homelessness, and Health. The first results, which surveyed 298 homeless people, were published in october.

Once a month, a growing number of PATHS participants in Los Angeles County receive a text message with a link to a 15-minute survey. Upon completion, they receive an electronic gift card. Though the survey process is simple, it requires a smartphone, which has 56% of Los Angeles County’s homeless population, according to a 2017 Henwood study.

PATHS isn’t the only technology-based outreach in the homelessness field, but few programs focus as aggressively on understanding people on an individual basis, especially in an area like Los Angeles County that deals systematically with homelessness. Homelessness.

For example, in addition to asking survey participants how many days it has been since they last stayed in temporary housing, the survey also asks how likely they are to accept a temporary housing option. Additionally, a question focusing on the last time someone was removed from a tent camp for not obeying a city ordinance might be followed by a question about whether participants believe they understand the local camping laws that police them.

“When you do a study like this and really talk to people instead of just looking at the numbers, it really makes the problem more human,” said Donald Whitehead, who experienced homelessness and is now executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless. Non-profit home.

With the data collected so far, PATHS appears to be addressing these questions and challenging some common beliefs about homelessness.

One such myth is that experiencing homelessness is a choice that people make and actively choose to maintain. The PATHS study found that 90% of participants would be interested in some form of temporary or permanent housing.

One-third of those surveyed said they are currently on a housing waiting list, while another third reported that they did not participate in any type of outreach.

Another surprising finding from the study was that only a quarter of the respondents felt informed about Los Angeles County Camping Lawsthat have been used to crack down on homeless people living in tents.

“If you’re going to monitor a population, you probably need to know what laws are being applied,” Henwood said. “What’s being offered isn’t housing that’s meant to be permanent, it’s not something that’s really designed to help someone get back on their feet,” he said.

PATHS also maintains individual records of people over a period of time. This means that, in a matter of seconds, a researcher can open a person’s file and see the results of their previous monthly survey, providing information about their preferences over time, encounters with the police or the trend in their physical well-being. and mental, something that the teachers say. it is rare in homeless research.

«It’s incredibly valuable information.» We want to spend money on things that have an impact, and being able to see the big picture on a case-by-case basis is the most important thing,” said Steve Berg, policy director for the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Henwood and Kuhn said case managers, those who work with homeless individuals and families, do an exceptional job of monitoring people in their case notes, but not as completely and consistently as PATHS would.

“There has to be a system that can more easily track the person and allow them to check in, self-test and access health on their own, and phones provide an incredible conduit for that,” Kuhn said.

As of now, the monthly data collected by PATHS has no direct implications or informs policy decisions, but the researchers say they hope it can one day educate on helping the homeless.

«I hope we’ve designed this in a way that the data takes us where we need to go rather than where we think we need to go in advance,» Kuhn said.

The second round of surveys will be collected in January with a larger sample size and additional custom questions focused on negative police encounters.