The moon is hot right now.

By some estimates, as many as 100 lunar missions could launch into space over the next decade, a level of interest in the moon that far exceeds the Cold War-era space race that saw the first humans set foot on the lunar surface.

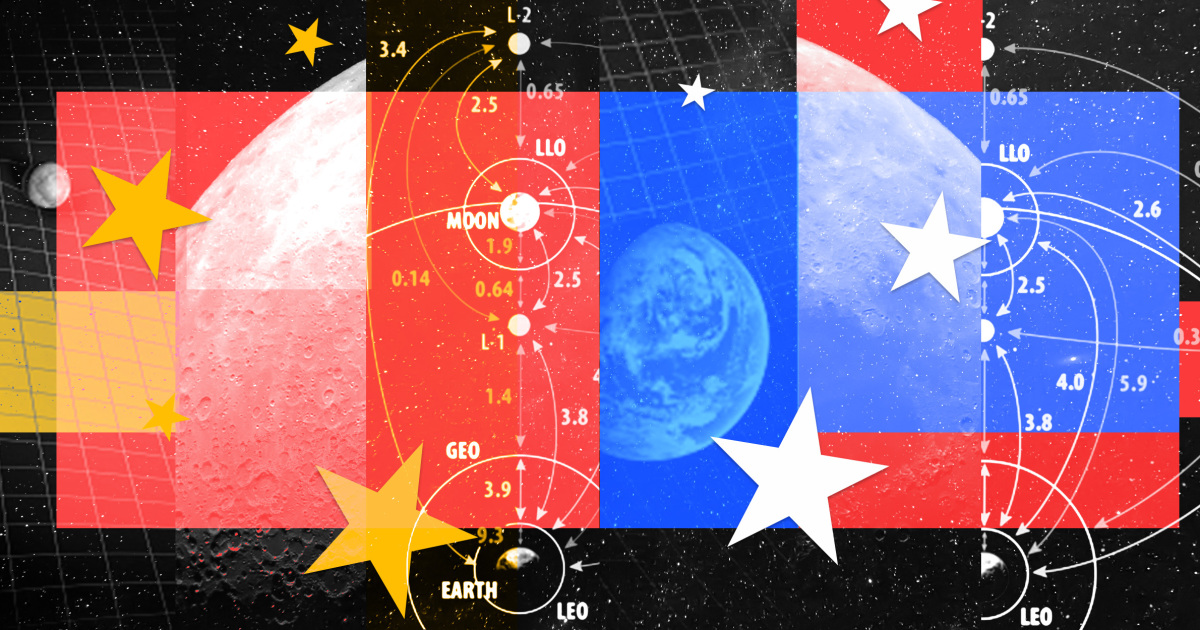

With multiple nations and private companies now setting their sights on moon missions, experts say cislunar space, the area between Earth and the moon, could become strategically important, potentially opening up competition for resources and positioning. and even provoking geopolitical conflicts.

“We are already seeing this competing rhetoric between the US government and the Chinese government,” said Laura Forczyk, chief executive of Astralytical, an Atlanta-based space consulting firm. “The United States points to China and says, ‘We need to fund our space initiatives on the Moon and cislunar space because China is trying to get there and claim territory.’ And then Chinese politicians are saying the same thing about America.»

Both the US and China have robust lunar exploration programs in the works, with plans not only to land astronauts on the moon, but also to build surface habitats and infrastructure in orbit. They’re not the only nations interested in the moon, either: South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, India and Russia are among the other countries with planned robotic missions.

Even commercial companies have lunar ambitions, with SpaceX preparing to launch a private crew this year on a tourist flight into lunar orbit, and other private companies in the US, Japan and Israel racing to the moon.

Greater access to space, and to the moon, brings many benefits to humanity, but it also increases the potential for tensions over competing interests, which experts say could have far-reaching economic and political consequences.

“During the Cold War, the space race was about national power and prestige,” said Kaitlyn Johnson, deputy director and fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Aerospace Security Project. «Now, we have a better understanding of the kind of benefits that operating in cislunar space can bring to countries back home.»

Although definitions sometimes differ, cislunar space generally refers to the space between Earth and the moon, including the moon’s surface and orbit. Any nation or entity that intends to establish a presence on the moon, or that has ambitions to explore deeper into the solar system, has a vested interest in operating in cislunar space, whether with communication and navigation satellites or outposts that serve as way stations between Earth and the moon

With so many lunar missions planned for the next decade, space agencies and commercial companies will likely be looking at strategic orbits and trajectories, Forczyk said.

«It may seem like space is big, but the specific orbits we’re most interested in fill up quickly,» he added.

Much of the increase in activity in cislunar space is due to substantial reductions in launch costs over the past decade, with technological advances and increased competition driving down the price of sending objects into orbit. At the same time, planetary science missions have given humanity a glimpse of the resources available in space, from ice deposits on the moon to precious metals on asteroids, said Marcus Holzinger, associate professor of aerospace engineering sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder.

«Once people really started thinking about it, they realized that water ice can either provide substantial resources or allow for the harvesting or harvesting of resources in other parts of the solar system,» he said.

Water ice can, for example, help sustain human colonies on the moon, or split into oxygen and hydrogen to power rockets on longer journeys into deep space.

With so much to gain, conflicts could arise between nations or commercial entities.

In 2021, Holzinger co-authored a report titled “An introduction to cislunar space“ to help US government officials understand the ins and outs of cislunar space. Holzinger said it was not meant to be a strategy document, but rather to inform the military and the government that are interested in cislunar operations.

That interest is evident: Last year, the Space Force identified cislunar operations as a development priority, and in April it established the 19th Space Defense Squadron to oversee cislunar space. In November, the The White House launched its own strategy for inter-institutional research on «responsible, peaceful and sustainable exploration and use of cislunar space».

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, with more than 110 countries counted as parties, essentially stated that the exploration and use of outer space should benefit all of humanity and that no country can claim or occupy any part of the cosmos. More recently, the Artemis Accords signed in 2020 established non-binding, multilateral agreements between the US and more than a dozen nations to maintain peaceful and transparent space exploration.

Holzinger said these deals are «easy» when there are no tangible economic and geopolitical interests at stake.

“Now we are seeing rubber hit the road, because suddenly there are potentially geopolitical or commercial interests,” he said. «Maybe we need to come up with a more nuanced approach.»

Creating a sustainable and safe environment for cislunar operations will be critical, but the very nature of this area presents its own challenges.

Situational awareness in cislunar space, or the ability to know where objects are at all times, is complicated because of its expansion compared to the volume of space around Earth, including low-Earth orbit and geostationary orbit, he said. Patrick Binning, who oversees programs on space solutions to national security challenges at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

«The volume of cislunar compared to the volume below geostationary orbit is 2,000 times more volume, so finding things and keeping track of things in that huge volume is a huge challenge.» he said.

It is also harder to detect satellites and other spacecraft at such great distances from Earth, and in some cases harder to predict their trajectories.

This is because objects in cislunar orbit are influenced by three different gravitational forces: Earth, the Moon and the Sun, Johnson said.

«It’s a three-body system, which means that not all orbits are nice and circular or as predictable as near-Earth orbit,» he said.

Together, these factors could make it difficult to manage traffic in the cislunar space, particularly if adversaries intentionally attempt to mask their activities there.

However, if humans intend to establish a permanent presence on the moon and venture beyond Mars, it will be imperative to prioritize safety, sustainability and transparency, said Jim Myers, senior vice president of The Aerospace’s civil systems group. Corporation, a federal corporation. funded research organization based in El Segundo, California.

«Those elements have to be there,» Myers said. «Unless we do this in a very thoughtful way, unless we plan, we’re going to run into all kinds of problems.»