Although much of the brain remains a mystery, scientists have long surmised that our thoughts, feelings, and behavior are the result of billions of interconnected neurons that relay signals to one another, enabling communication between brain regions. .

but a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature challenges that idea, suggesting instead that the shape of the brain — its size, curves, and grooves — may exert a greater influence on how we think, feel and behave than the connections and signals between neurons.

A research team in Australia came to that conclusion after taking MRIs of the brains of 255 people while the participants performed tasks such as tapping with their fingers or recalling a sequence of images. From there, the team examined 10,000 different maps of people’s brain activity, collected from more than 1,000 experiments around the world, to further assess the role of brain shape.

They then created a computer model that simulated how the size and shape of the brain affect waves of electrical activity, better known as brain waves. They compared that model to a pre-existing computer model of brain activity that aligns closely with the understanding of neural connectivity as a driver of brain function.

The comparison showed that the new model provided a more accurate reconstruction of brain activity shown on MRIs and brain activity maps than the older model.

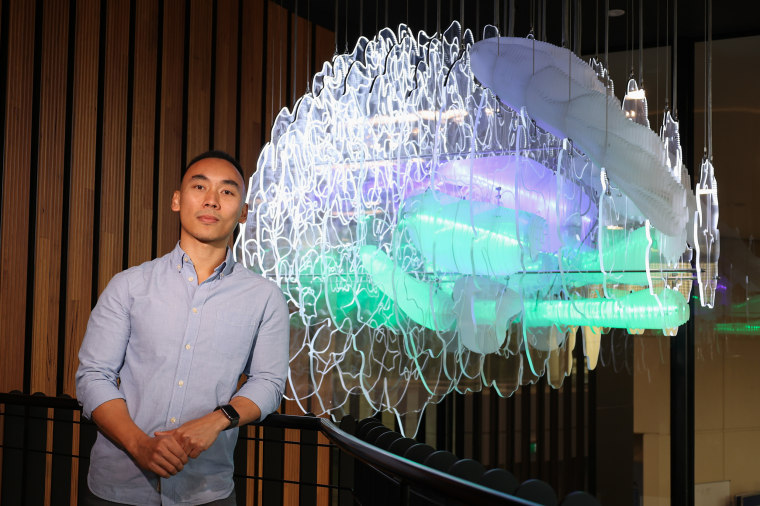

James Pang, lead author of the study and a researcher at Monash University in Australia, compared the importance of brain shape to a stone making ripples in a pond: the size and shape of the pond help determine the nature of those ripples. .

«The geometry is quite important because it guides what the wave would look like, which in turn relates to the activity patterns seen when people perform different tasks,» Pang said.

David Van Essen, a professor of neuroscience at Washington University in St. Louis, said the brain shape theory has been floating around for more than a decade. But most researchers, he said, still subscribe to the classical hypothesis: that each of the brain’s nearly 100 billion neurons, or nerve cells, has an axon, which functions as a cable to carry information to other neurons, and that allows brain activity.

«The fundamental initial hypothesis is that the brain’s wiring is critical to understanding how the brain works,» Van Essen said.

Pang said his research doesn’t discount the importance of communication between neurons; rather, she suggests that brain geometry plays a more essential role in brain function.

«What the work shows is that shape has a stronger influence, but it doesn’t mean connectivity isn’t important,» he said.

Pang also noted that the brain shape hypothesis has an advantage: The shape of the brain is easier to measure than the brain’s wiring, so paying more attention to the size or curves of the brain could open up new avenues for research. .

One topic worth exploring, he said, is the possible role of brain shape in the development of psychiatric and neurological diseases.

In theory, Pang said, the speed at which traveling waves propagate to different regions of the brain could affect how people process information. That, in turn, could contribute to patterns of brain activity associated with diseases such as schizophrenia or depression.

But not all scientists are convinced by the new research. Van Essen, for example, remains skeptical.

«It would be an understatement to say that this is a controversial theory, and it really needs to be put to the test to critically assess whether it stands the test of time,» he said.

Van Essen raised several concerns about the study, including the fact that the researchers’ models are based on an average of the shapes of the participants’ brains. According to Van Essen, that approach overlooks the dramatic differences in the patterns of surface folds from one brain to another.

Pang, however, said the findings «remain robust» even after taking an individual-level analysis of brain shape.

Van Essen also cautioned that MRIs are imperfect tools and may not reliably capture the nature of the brain’s wiring.

«As exciting and informative as it is, it is still fundamentally inaccurate and incomplete, leaving much to be resolved in future studies,» he said of the MRI technology.

Pang said his research is not definitive, but added that he believes the new study «strengthens the theory» that the shape of the brain has a greater influence on brain activity than the wiring of neurons.

«We’re pretty sure the influence is really there,» he said.