The story of the adolescent chronicler Anne Frank is known throughout the world. But a new survey suggests a «disturbing» lack of awareness about the Holocaust in the Netherlands, where she and her family hid for years before being discovered and deported to a Nazi concentration camp.

A Dutch Holocaust survivor and Jewish cultural leaders expressed dismay at the poll, which was released Wednesday and suggested more than half of residents were unaware of the deportation and murder of the country’s Jews during World War II.

He pollconducted and published by the New York-based nonprofit Claims Conference ahead of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Friday, found that 53% of respondents were unable to identify the Netherlands as a country where the events occurred. of the Holocaust, increasing to 60% among millennial and Gen Z respondents, that is, those under 40 years of age.

Historians estimate that more than 70% of the pre-war Jewish population of the Netherlands was killed during the Holocaust, more than 100,000 in all. Frank hid in a secret room in Amsterdam with his family from 1942 to 1944 before dying in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp weeks before his release.

Despite the extensive available evidence of the systematic killing of 6 million Jews, 12% of those surveyed told researchers that the Holocaust was a myth or that the number of deaths was grossly exaggerated, the highest figure for any of the the six nations surveyed in recent years. years. For the Netherlands, this rises to 23% of people under the age of 40.

Earlier research by the Claims Conference found that 15% of American youth also doubted the historical record of the Holocaust.

“Survey after survey, we continue to witness a decline in knowledge and awareness of the Holocaust. Equally troubling is the trend toward denial and distortion of the Holocaust,» Claims Conference Chairman Gideon Taylor said in a news release accompanying the survey, which was released Wednesday.

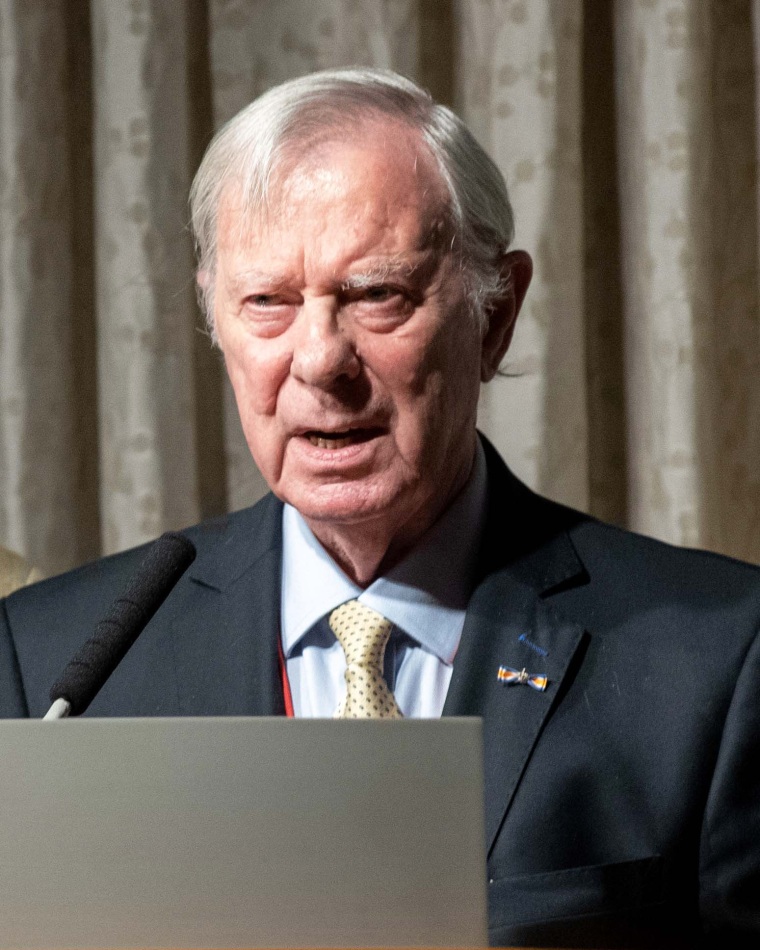

“It was disturbing to see that a large number of my compatriots, of whatever religion they are, do not know enough about the Holocaust. Some of them, a small part, don’t even know about the Holocaust,” Dutch Holocaust survivor Max Arpels Lezer, 86, told NBC News by video call from his home in Amsterdam.

After Jews began to be deported from the Netherlands, Lezer was sent from Amsterdam at the age of six to live with a foster family in the rural region of Friesland in the north of the country. He lived there with Ype and Boukje Wetterauw for six years and was never betrayed by the townspeople, where he stood out with his black hair and unusual name. The Wetterauws’ only child had previously died in infancy.

Today, Lezer has warm memories of a dark time. He remained close to the Wetterauws until they died and was named in his will. “I really was his son,” he said.

A wooden horse and cart which he played alongside his adoptive brother, Gerrit, is now in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Lezer spent years searching for his adoptive sister, Joke, who briefly lived with the family, to no avail.

Many other children who went into hiding, like Anne Frank, were not so lucky, as she has told countless classes of children over the years.

“When you sit in front of a class and you have students sitting on their stools, they hear a guy come talking about the Holocaust and they all do this and start snoring,” she said, slumping back in her chair and closing her eyes. .

“When you lived through the Holocaust, it takes a lot of courage to continue this kind of work. Maybe in other countries this attitude is different, but I live here”.

A ‘red flag’ for education

Emile Schrijver, director general of the Jewish Cultural Quarter in Amsterdam, told NBC News that the survey results should act as a «red flag» for how schools deal with the Holocaust.

“That a third of young people feel that this may never have happened, that the numbers are wrong, that is shocking. The answer is clear, there is only one practical answer: education, education and education, ”she said.

Schrijver noted that during protests against the Netherlands’ strict social gathering rules during the Covid-19 pandemic, some protesters used yellow stars to imitate the insignia that Jews were forced to wear in Nazi-occupied countries, in an attempt to illustrate state persecution.

“We have a society where conspiracy theories are considered normal, where people wore yellow stars during Covid protests, which a lot of people seemed not to oppose. The surprising fact is not that people do that, there will always be idiots, it’s that people didn’t object,» said Schrijver, who is working on the new National Holocaust Museumwhich will open in Amsterdam in September.

Mayor of Amsterdam Femke Halsema condemned the protesters with yellow stars, Schrijver notes, but said national politicians were much slower.

The Netherlands plays a relatively small role in the Holocaust story, but it is important for understanding the full story, said historian Anna Hájková, of the University of Warwick in England.

“In the Western European context, many Dutch Jews were disproportionately rounded up and deported. On top of that, disproportionately many Jews from the Netherlands who were deported died,” he said.

Hájková’s work has shown that around 70% of the Jews of the Netherlands, 100,657 people, were deported from the Netherlands between July 1942 and September 1944, of whom 57,552 were sent to Auschwitz. Only 854 returned, a very low survival rate compared to other countries.

“So Holland, for a normal person who reads the newspaper, they may not know why Holland is special. But for us as Holocaust historians, when you pay attention to the details, it’s extraordinary,” Hájková said.

The prospect of terror was never too far away.

A man, the father of a friend, who was a collaborator with the Nazis, confronted Lezer as he and his friends were walking towards the seashore.

“It wasn’t an actual uniform, but something like that anyway, with shiny black boots,” Lezer recalled of what the man was wearing. “He looked at each child and told me: ‘I know you are a Jewish child, we will come to find you.’ And he pointed his finger at his chest and I was so afraid that I fell backwards on the ground. My clothes turned dark blue between my legs.»

Lezer’s mother died in Auschwitz, but he was reunited with his father in 1948. At first, Lezer thought his stepmother was his biological mother, but he later learned the truth from a member of the Amsterdam Jewish congregation. He says he suffered physical and emotional abuse at the hands of his stepmother, memories that are still hard to relive after all this time, and three times he ran away to be with the Wetterauws, once cycling 12 hours to get there.

In 1961, Lezer married 86-year-old Sofia, another Jewish girl hidden by a Dutch family during the war.

Having lived and survived such horror, Lezer is in no doubt of the imperative that the history of the Holocaust never fade from memory.

«Because if you don’t know enough about the Holocaust and you don’t know that so many people died because of Nazi persecution,» he said, «then you don’t know enough to be realistic about the future.»