A decade after the era of the HIV prevention pill, called PrEP, efforts to harness its heralded power to curb new infections have stalled in the United States.

This shortfall is a key reason the nation lags far behind many others in the fight against HIV, with a national epidemic plagued by racial inequities and a modestly declining rate of new infections.

“We are reaching a scientific crisis in HIV prevention,” LaRon Nelson, an associate professor of nursing and public health at Yale University, said last month at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle. Nelson lamented the gulf between PrEP’s impressive performance in major studies and its moderate impact in the real world.

On the bright side, PrEP, which is short for pre-exposure prophylaxis and involves taking oral or injectable prescription antiretroviral drugs before possible exposure to HIV, has achieved substantial popularity, but only among gay and white men. bisexuals, who have a long experience. seen a drop in the HIV rate.

Such inequity persists despite the efforts of a nationwide public health army and the untold millions of dollars spent to promote and facilitate the use of PrEP among Black and Latino gay and bisexual men. Of all the major intersectional demographic groups, these groups contract HIV at the highest rates, and transmissions between them have either plateaued or only slightly decreased in recent years.

And so, even in the midst of a national reckoning over racial inequity, PrEP has only served to widen racial disparities in HIV transmission among men who have sex with men.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, gay and bisexual men represent 70% of new cases of the virus. Whites in this demographic made up of 15% of the 34,800 HIV transmissions in 2019, while the much smaller populations of their Black and Latino peers respectively comprised 26% and 23% of new cases.

Also, more than a year after the approval of a long-acting injectable form of PrEP, ViiV Healthcare’s Apretude, few are receiving it. Insurers have mostly refused to cover the expensive drug. Consequently, even after clinical trials found that injectable PrEP was dramatically higher to oral PrEP in HIV prevention at the public health level, especially among black gay men, the potential of Apretude will likely remain untapped for the foreseeable future.

Worrying Statistics

Gilead Sciences’ Truvada two-drug combination pill was approved as PrEP in 2012 and has been followed in 2019 for a similar drug, Descovy. When either drug is taken daily, this reduces the risk of HIV by at least 99% among gay and bisexual men and transgender women, according to multiple studies.

PrEP has helped reduce HIV rates in cities where it has reached a critical mass of popularity, such as in NY, San Francisco and Seattle. But nationally, PrEP has failed to move the needle by much.

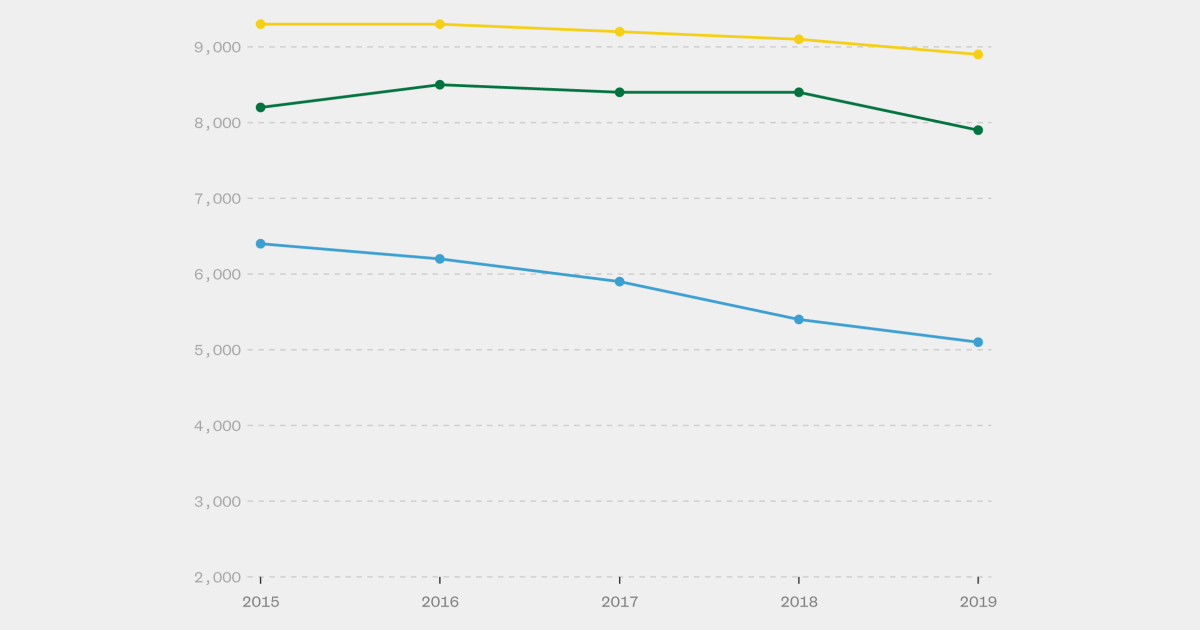

CDC Estimates Annual HIV Transmissions decreased only 8% between 2015 and 2019. Cases are even rising in some states where investment in HIV prevention is lacking, such as Tennessee, where Republican Gov. Bill Lee recently compounded the factors worsening his state’s epidemic by blocking $8.3 million in annual prevention funding from the CDC.

Approximately 814,000 gay and bisexual men in the US are good candidates for PrEP, CDC estimates. Between 2017 and 2022, the number of people using PrEP, who have always been overwhelmingly gay and bisexual men, at any time during each year increased from 155,000 to 382,000. However, a CDC study presented in Seattle found that as of September 2022, only 187,000 people were taking PrEP within that 30-day period, suggesting that many people don’t take it for very long.

The growing popularity of PrEP likely could have put a dent in the national HIV rate if its use had more closely mirrored the demographics of viral transmission, according to HIV prevention experts. Of the CDC estimate of 21,900 new HIV cases in 2019 (the most recent year for which the agency produced a transmission estimate) in the three largest racial groups among gay and bisexual men, 23%, 41%, and 36% respectively were white, black and Latino. But an unbalanced 69% percent of PrEP users last year they were white, while only 9% and 18% respectively were black and Latino.

Aprudede’s approval promised progress

Approved in December 2021, Apretude requires a healthcare worker to give you an injection every two months. Compared with giving trans women and men who have sex with men Truvada as PrEP, giving them Apretude was associated with a 66% lower overall HIV diagnosis rate over a major clinical trial.

The superior efficacy of Apretude was driven by the fact that participants adhered better to the injection schedule than to the daily pill regimen.

Dr. Hyman Scott, an HIV prevention expert at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, reported at the Seattle conference that of the 844 black American participants in the trial, those randomly assigned to receive the injectable drug had a rate HIV 72% lower than those who got Truvada.

Their analysis suggests that if 10,000 black gay and bisexual men and trans women were followed for a year, approximately 50 would contract HIV if given Apretude, while 200 would test positive if given Truvada.

Such sobering findings about Truvada’s shortcomings are in keeping with former studies finding relatively low rates of adherence to daily PrEP regimen among black gay men. Such data suggests that even if HIV prevention advocates were to greatly increase access to oral PrEP in this population, it might have only limited impact among them.

Referring to Apretude, Scott told NBC News: «The real question is can we implement this in communities.»

Cost is a major issue. Since 2021, Truvada has been available through multiple generic manufacturers and now often costs as little as $25 to $35 per month, though in some cases up to $600. ViiV lists Apretude at $1,878 per month, and few insurers cover it.

The recent CDC PrEP use study presented in Seattle found that only about 1 in 200 PrEP prescriptions were for Apretude in September.

“There are patients who are getting Apretude now, but they are the people who have access to healthcare, who are knowledgeable about healthcare, who are calling their insurance companies and yelling at the right people,” said Dr. Anu Hazra, LGBTQ-focused physician at Howard Brown Health in Chicago.

As of 2021, nearly all insurers are required under the Affordable Care Act to cover oral PrEP with no out-of-pocket costs for medications or quarterly clinic visits and lab tests needed to maintain a recipe. This is because in 2019an advisory body known as the US Preventive Services Task Force gave PrEP an «A» rating for being a valuable preventive tool.

In December, the working group issued a draft decision awarding Apretude its own «A» rating. If this rating becomes official this year, insurers will need to cover Apretude and no cost share, but not until January 2025.

fitness upgrades

In addition to the associated burden of having to come in six times a year for injections, Apretude has one notable shortcoming: Apparently, advanced HIV cases are much more likely among those taking injectable versus oral PrEP.

According to a presentation in Seattle by Dr. Susan Eshleman, a professor of pathology at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Eshleman’s team has yet to calculate Apretude’s per capita infection breakthrough rate, but when these researchers initially reported last year that seven infection breakthroughs were observed in the trial (before reducing this number to six), their calculations suggested that if 10,000 similar trans men and women were followed for a year, 15 would contract HIV despite receiving the Apretude injections on schedule.

At the same Seattle conference, Hazra reported the first case of HIV breakthrough in an Apretude patient outside of a clinical trial. By comparison, it took almost four years after Truvada’s approval as a PrEP before advanced infection was detected. first documented on someone faithfully taking that drug.

To date, there has been a handful of other case study reports of HIV breakthrough in people taking oral PrEP. Yet there has only ever been a clear case in major clinical trials that include Truvada or Descovy as prevention.

All of this suggests that for those with a history of taking oral PrEP every day as scheduled, switching to Apretude would actually increase their risk of contracting HIV; although the absolute risk of infection would still be low.

Optimism in the pipeline

HIV prevention experts report that they are excited about the PrEP pipeline and hope that more convenient and longer-acting forms will be approved in the next decade.

“I’m tremendously optimistic,” said Sharon Hillier, a leading HIV prevention researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. “We just have to work on how to deliver these interventions and how to be less burdensome on health care systems.”

The Seattle conference heard promising early-stage research findings regarding drug-infused suppositories that could be placed in the rectum or vagina for up to 48 hours after sex and likely prevent HIV. And researchers are developing implants that could be placed under the skin and deliver preventative drugs for many months.

Gilead is also major race PrEP trials of the drug lenacapavir, which only requires one injection every six months. Dr. Jared Baeten, who leads Gilead’s HIV strategy, said the company expects to provide initial study results by 2025.

But if Apretude’s timing is any guide, it could be 2030 before lenacapavir is approved and widely covered by insurers.

Meanwhile, PrEP advocates continue to express their dedication to working with the options currently on the table, albeit within a complex and fractured health care system that is alienating for many of those most at risk of HIV. .