A recently released internal 2017 Veterans Affairs report shows that black veterans were denied PTSD benefits more often than their white counterparts.

The analysis analyzed claims data from fiscal year 2011 through 2016 and showed that African-American veterans seeking PTSD disability benefits were denied 57% of the time, compared to 43% for white veterans. The report emerged as part of an open records lawsuit filed by an advocacy group for black veterans.

Terrence Hayes, a spokesman for the Department of Veterans Affairs, said the agency did not immediately have updated data on a racial breakdown of PTSD disability benefit awards and said the agency «is collecting the data and will share it once we are fully compiled.

Hayes wrote in an email that the agency could not comment on any ongoing litigation, but that VA Secretary Denis McDonough is committed to addressing racial disparities when it comes to VA benefits.

Hayes noted that earlier this month, McDonough acknowledged the disparities and announced the creation of an Equity Team, telling reporters: «The first order of business for that team will be to investigate the disparities in grant rates for black veterans.» , as well as all minority and historically underserved veterans. – and delete them.”

Richard Brookshire, a black veteran who served in Afghanistan as a combat medic, co-founded the Black Veterans Project in Baltimore, which filed the freedom of information request lawsuit. He says he’s frustrated that the government aggressively recruits black soldiers from black neighborhoods, but the VA can’t share data on disparities. “If they don’t know, it’s because they don’t want to know,” he said in an interview with NBC Washington.

Brookshire said the VA initially provided it with raw data from 2002 to 2020 that was analyzed by a Columbia University team, and the data showed disparities, but the VA did not share its 2017 analysis until it filed the FOIA complaint.

The 2017 analysis is significant because investigation has shown that minority veterans had higher rates (5.8%) of PTSD than non-minority veterans (5%). Black Vietnam veterans were found to have higher rates of PTSD, in part because they were more likely to be in combat than their white counterparts.

The disparities were highlighted in a series of reports by NBC News Now and local NBC stations in a series called «American Veterinarians: Benefits, Breed, and Inequality.«

‘I would wake up fighting’

Ronnie Forbes, a black veteran living in Livermore, California, enlisted in the Army in 1984 and was deployed to Korea, where he was stationed in the Demilitarized Zone. He says that’s where he developed PTSD from living in a constant state of readiness. «I couldn’t sleep at night, he was hearing all kinds of things and anxiety attacks,» he said. NBC Bay Area Reporter Bigad Shaban.

In 2015, he filed a PTSD service-connected disability claim with the VA. Nine months later, the VA turned him down. With the help of advocacy groups, he appealed the VA’s decision multiple times and received retroactive approval last month, seven years after his initial denial.

Forbes told Shaban that he believes racism played a role in his years-long pursuit of PTSD benefits. “I dealt with this in the military and now out of the military,” he said. «As a veteran, I am dealing with the same issues through this appeals process.»

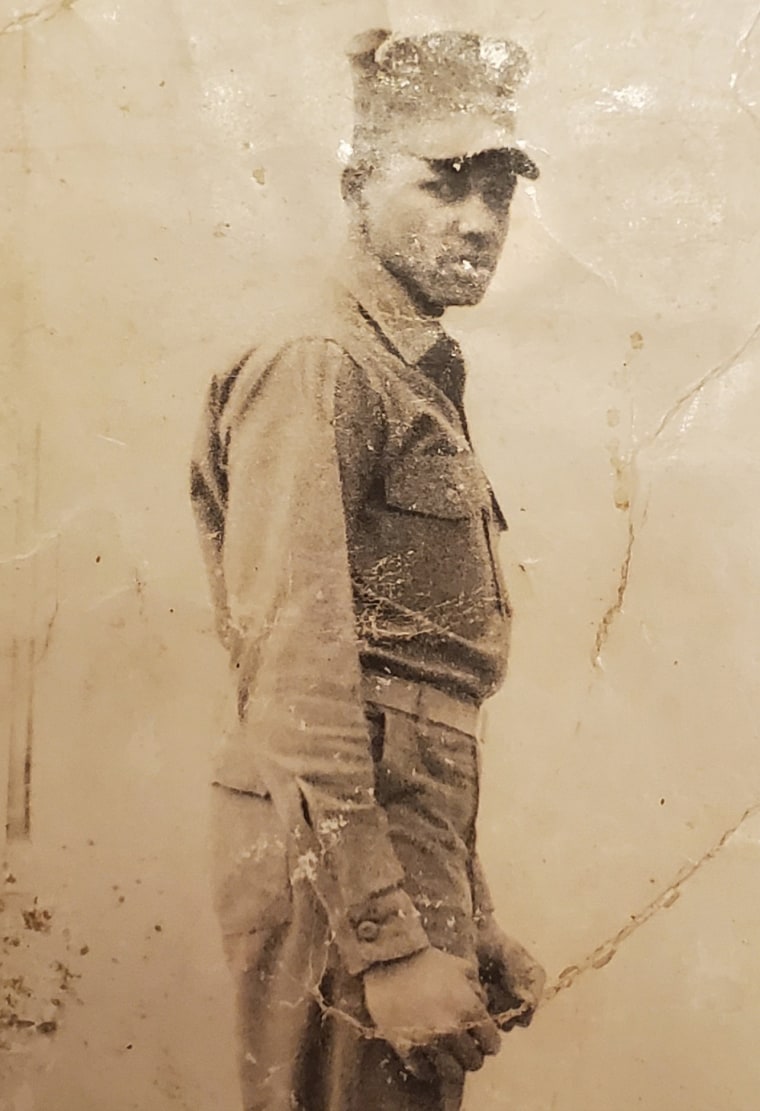

Conley Monk Jr., 74, of Connecticut, served as a Marine in Vietnam and says he remains haunted by a gruesome incident in which a fellow Marine ran over a Vietnamese man right in front of him. He says that he did not know at the time that this incident and the violence he witnessed in Vietnam had contributed to his post-traumatic stress disorder. “Ever since I got back from Vietnam, I knew I had a problem, but I didn’t know what it was. I knew that every time I would get angry when someone put their hands on me, I would react and get in trouble.

Monk says that after his service in Vietnam, he was transferred to Okinawa, where he had two altercations that he attributes in part to a «constant state of fear and hypervigilance,» according to court documents.

He said NBC Connecticut reporter Kyle Jones in Hartford who often slept poorly. “You know, my sisters, or brothers, anyone who put their hand on me, I would wake up fighting. I knew then that she had a problem. But I didn’t know the name of that.»

He says that after the riots in Okinawa, he agreed to an «undesirable dismissal» but did not understand that it could negatively affect his eligibility for VA benefits. Monk says it took 40 years for his discharge to be reversed.

In early March, Secretary McDonough said the agency was «struggling with race-based disparities in VA benefit decisions and military discharge status.»

Forbes told Shaban that he is grateful that the department acknowledges that they fell short. “I’m a little relieved that they’re acknowledging what’s going on. That’s kind of a relief to me,» he said. «Now we know what the problem is. Now let’s work on the solution.»

This article was published by Lucy Bustamante in NBC Philadelphia, Kyle Jones and Katherine Loy in NBC Connecticut, Tracee Wilkins and Rick Yarborough in NBC Washington, Bigad Shaban and Michael Bott in NBC Bay Area, Mark Mullen and Mike Dorfman in NBC San Diego, Noreen O’Donnell of NBCU Local and Laura Strickler of the NBC News Investigative Unit.